Spoiler warning: This article contains spoilers for “The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes.”

The world of Panem depicted in “The Hunger Games” franchise is not foreign to our generation. A significant portion of Gen Z grew up reading the acclaimed trilogy by Suzanne Collins, and many also grew up watching the movies. The original films, “The Hunger Games,” “The Hunger Games: Catching Fire,” “The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 1” and “The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 2” were released between 2012 and 2015, and nearly a decade later, the newest installment in the franchise, “The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes,” released on Nov. 17. This film is more harrowing and gripping than those that came before it, and its dark themes prove the franchise has matured with its audience.

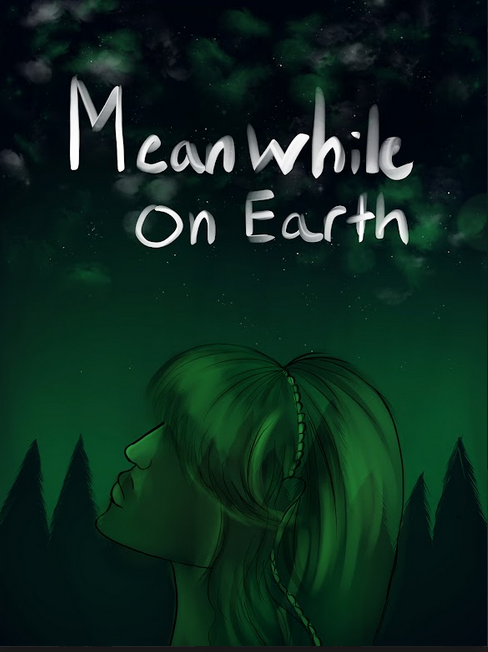

Based on the novel released in 2020, “The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes” takes the audience back to Panem, as the story is set 64 years before we meet Katniss Everdeen. This prequel follows a young Coriolanus “Coryo” Snow, played by Tom Blyth, chronicling his young life and, as well as his descent into the malicious tyrant from the original trilogy. The film also follows Lucy Gray Baird, played by Rachel Zegler, a girl from District 12 who becomes a tribute in the 10th annual Hunger Games. As tribute and mentor, Lucy and Cory’s fates are intertwined with the mission of Lucy becoming a victor, and within this ordeal, the true nature of the Capitol is revealed. While the film primarily focuses on the games, several details woven into the plot show that, like its predecessors, this film does not shy away from its societal commentary.

Several details throughout the film are blatant reminders of the real world and how our governments treat their people. One example of this is how the roots of the Hunger Games are just as inhumane as audiences have always thought them to be — maybe even more so. In the film, the tributes are starved, caged in a zoo and not allowed to shower, and people from the Capitol mock them and gawk at them like animals. This shows that not only are the games about killing children, but they are also about stripping tributes of their dignity and showing the districts that anyone, even the sick and disabled, is able to be punished and disposed of. Another example that comes to mind is how the people in the Capitol care more about symbols than they do about actual lives. In our society, especially in America, the flag is treated with the utmost respect and importance, and any disregard or defilement of the flag and what it represents is met with shock and anger. This can also be said for the Capitol people; a scene in the movie shows a tribute in the arena tearing down the flag of Panem, and the audience members gasp with horror as he drags it across the ground. These are the same people who watch children murder each other each year for entertainment, and turning a blind eye to the killing of innocents yet protesting the disrespect of a symbol acts as an undeniable reflection of the world we live in. Though these are just a couple of examples, they still show that the franchise remains the acute societal critique that it is known as.

Outside of plot details, the film itself looks fantastic. Bringing back Francis Lawrence, the director of the second, third and fourth installments in the franchise, was the perfect choice. It led to the film feeling exactly like its predecessors, despite looking more modern. The film’s cinematography is more clear than those before it, but the design of Panem — the Capitol, the districts, the sets, the outfits — leaves the audience feeling like the eight-year gap between the last installment and this one is non-existent.

This feeling is also driven home by the performances in the film. Blyth’s performance is nothing short of stellar; his portrayal of Snow is nuanced and even makes the audience want to root for him during a few scenes, despite the knowledge of who he becomes. He depicts a boy doing what he believes is best until doing so takes him past the point of no return. Alongside him, Rachel Zegler is a shining star as Lucy Gray. Many people have mixed feelings about her given her comments about the upcoming live-action adaptation of “Snow White,” in which she plays the titular role, but after this film, her sheer talent will be undeniable. Her portrayal of Lucy Gray is raw, at times humorous, and profoundly earnest, and the character is only elevated by Zegler’s talent not only as an actress but as a singer. Singing is an integral part of Lucy Gray’s character, and Zegler completely delivers with a voice that is equal parts powerful and mesmerizing. One of the best examples of this is when she sings “Pure As The Driven Snow,” a song that would not be as memorable without Zegler’s melodic voice. These performances, along with Hunter Schafer’s portrayal of Tigris Snow, Josh Andrés Rivera’s portrayal of Sejanus Plinth and Viola Davis’ portrayal of Head Gamemaker Dr. Volumnia Gaul, breathe the same life back into Panem that was present in the original trilogy.

Like its predecessors, this film resonated deeply with both long-time fans of the series and those new to Panem, which has allowed it to gross $100 million worldwide. “The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes” is an installment in the acclaimed “Hunger Games” franchise that includes incredible world-building, great performances and societal commentary that proves these dystopian films are not so dystopian after all. Set in a world filled with war, wealth inequality, poverty and subjugation, among other evils, this film is more reflective than ever of the society that we live in.