Adigwe, The Paisano

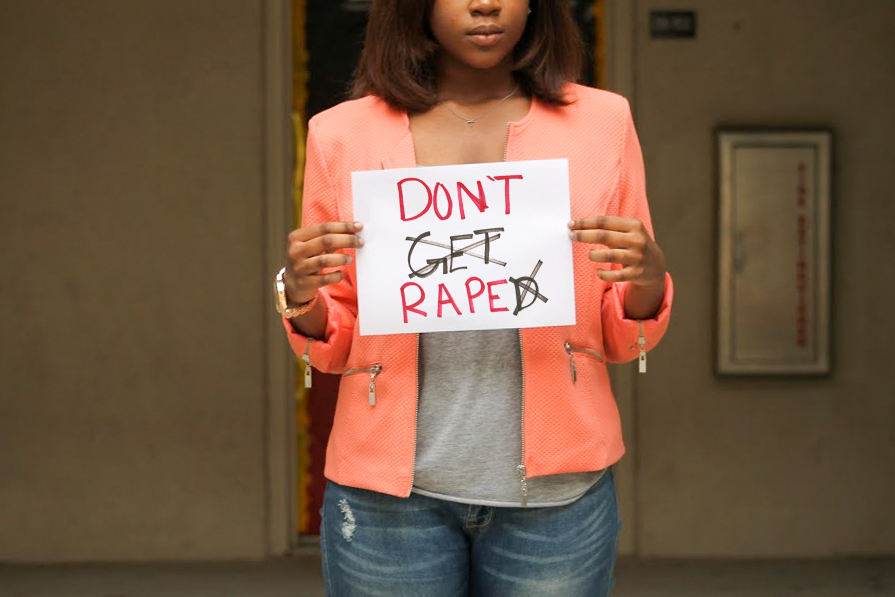

Nearly one in five women in America is a survivor of rape or attempted rape.

Despite such a statistic, crimes of sexual assault typically go underreported on college campuses across the country.

A potential explanation for this underreporting comes from current police proceedings in sexual assault cases.

A junior political science major student here at UTSA who wishes to go unnamed commented on the current system. “I was raped over Christmas break (Dec. 2015.) When the police came, they asked if I was intoxicated and treated me like I was wasting their time and resources. The way they treated me was almost as traumatizing as the rape itself. I felt like I didn’t have an advocate.”

According to a 2015 Association of American Universities (AAU) survey of 27 higher education institutions across the country, nearly one quarter of undergraduate collegiate women are victims of sexual assault. However, the rate of reporting following such crimes ranges from 5 to 28 percent.

Kimberly A. Lonsway and Joanne Archambault of the End Violence Against Women International organization found in a 2012 study that for every 100 instances of rape, only 5-20 rapes are reported. Of those, 0.4-5.4 individual offenders go on to be prosecuted, 0.2-5.2 are convicted and a mere 0.2-2.8 offenders face actual incarceration.

Data gathered from the AAU’s 2015 assessment revealed that 18.5 percent of UT Austin’s female undergraduate students had experienced some form of sexual assault. In response, the University of Texas System launched a $1.7 million, four-year study last August to reduce crime and promote safer, more conducive learning environments for students.

On March 1, the UT System announced the latest installment in the System’s study: “The Blueprint for Campus Police: Responding to Sexual Assault,” which is set to transform sexual assault culture, starting with methods law enforcement use to address such offenses.

Survivors of sexual assault might avoid pressing charges following a crime of this nature for many reasons. These survivors experience stigma, peer pressure, feelings of fear, guilt, shame and a myriad of other highly personal and difficult emotions.

However, much of these survivors’ underreporting can also be attributed to existing police protocols in responding to sexual assault cases.

Historically, survivors of sexual assault have been hesitant to approach law enforcement for fear they will not be taken seriously. Oftentimes, these survivors feel patronized by police officials — as though they are being met with “unwarranted skepticism.”

Many have been asked questions that victim-blame such as, “What were you wearing the night of the incident?” or “How much did you have to drink that night?”

Additionally, the sexual assault protocols used by law enforcement officials are not specifically oriented toward crimes of sexual assault. Police may rely on standard investigative procedures when dealing with sexual assault cases that prevent police from understanding the true nature of the assault, or how to accurately interpret survivors’ reports.

The UT System’s Blueprint aims to combat these barriers by integrating campus sexual assault research and sensitivity training into police protocol. By combining data with best practices, the Blueprint represents a corrective on myths surrounding campus sexual assault. In the words of the Blueprint’s primary author, Dr. Noël Busch-Armendariz, director of the Institute on Domestic Violence & Sexual Assault at the UT Austin School of Social Work, the document is “proof that science can and should inform police practice.”

All 170 pages of the Blueprint document were generated by UT System Police, UT Austin’s Institute on Domestic Violence & Sexual Assault and findings from the White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault.

The document serves as a guideline for law enforcement officials in dealing with cases of sexual assault. Police departments at each of the 14 UT System institutions are currently being trained on the Blueprint protocol — which takes into consideration each location’s unique culture and demographic.

The Blueprint opens by defining sexual assault and addressing common misconceptions regarding instances of sexual assault, such as myths that victims must be crying (or emotional), that they must have bruises and or other indications of struggle and that if alcohol is involved — the victim is partially to blame for what occurred.

The document then goes on to illustrate the prevalence of sexual assaults and rapes on college campuses, including a detailed report of each major UT institution’s reported sexual assault figures. The Blueprint’s data discloses that from 2011 to 2013, forcible sex offenses committed at UTSA’s main campus rose from two to six reported instances.

Following these statistics, the Blueprint gets into its groundbreaking material. The document utilizes neurobiological research, which illustrates what is happening for a survivor hormonally when he or she goes into a state of trauma. The research explains why a survivor might not have been able to fight off an assailant (as a result of tonic immobility — an autonomic, sexual assault-induced paralysis), or why he or she avoids eye contact and may allege events that are untrue. The research also explicates the role that alcohol and drugs play in the validity of a survivor’s account.

The Blueprint will guide law enforcement officials throughout cases of sexual assault, and its implementation fosters greater police-survivor communication and understanding of what survivors of sexual assault are going through. The document enables police departments to better proceed in helping survivors overcome such tragedies — whether legal action is pursued or not. As the introduction to the Blueprint explains, this comprehensive guide “replaces tradition with science.”

The impact of the Blueprint is projected to go beyond the scope of UT System institutions and influence the way other institutions address sexual assault in the U.S.

Dr. Amy Chanmugam of UTSA’s Social Work Department, College of Public Policy has already seen the influence that the Blueprint has had among the social work community, and she remains “hopeful that even beyond Texas, (the Blueprint) can contribute to compassionate responses and justice for sexual assault survivors.”