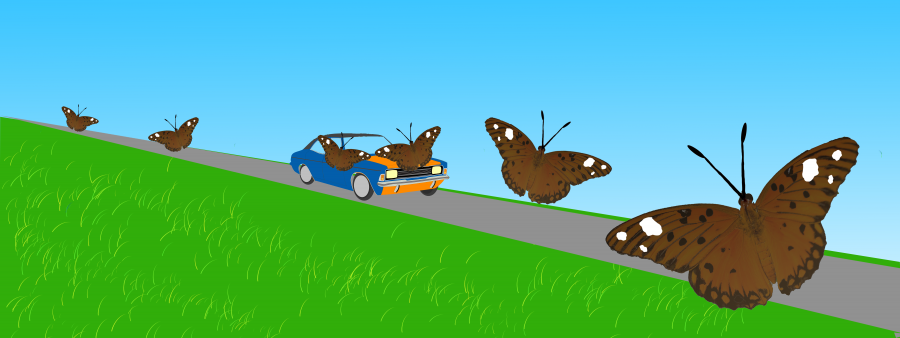

This September, San Antonio residents were surrounded by large clusters of butterflies. These butterflies are known as the American Snout, or “Snout nose.” These butterflies had lived in this region due to the abundance of Hackberry trees—the Snout’s host plant. But now, according to Texas entomologist Mike Quinn, “The Snout nose is ‘emigrating’ out of where they have overpopulated and exhausted the food source, looking for new mates.”

Roberto Guajardo Jr., a senior multidisciplinary studies major, said, “There are so many monarchs this year; I have never seen so many. The only thing is that I feel like every time I drive, I am killing a lot of them.”

Guajardo was not alone in thinking the butterflies splattering against his car were monarchs. Many people mistook these butterflies for the monarch butterfly.

Julian Chavez, an associate researcher for The Monarch and Milkweed Project at UTSA, has been taking these calls from frantic students and friends who believed they were killing monarch butterflies every time they drove. He clarified for these callers that they had their butterflies mixed up. The American Snout was their victim.

The Monarch and Milkweed Project, a 6.8 acre plot located on the Main campus, is dedicated to the research and preservation of the monarch butterfly and milkweed. Recently, this research project received a $300,000 grant from the Texas Comptroller. In April of this year, the area was designated a Certified Wildlife Habitat by the National Wildlife Federation.

Chavez explained what the researchers do:

“We are doing roadside surveys to figure out how much milkweed there is in Texas; we go from Pineland to Ozona and from Wichita Falls to Alice, stopping every 10 miles to make assessments,” he said. In these assessments, the team examines 750 square meters of every 10 miles to check for milkweed concentration alongside roads. In addition to the roadside surveys, the project team also does site specific surveys at different private properties.

Monarch butterflies change habitats like the American Snout does but for different reasons. Instead of being motivated by the search for food, monarchs migrate because they cannot withstand cold temperatures.

Their migration path covers 3000 miles from Canada to Mexico, and they travel from August to November. Every October, they pass through Texas. According to Chavez, over the last 10 years, the monarch butterfly population has declined 80 to 90 percent owing to deforestation, climate change, pesticide use and the loss of milkweed.

Unlike the relationship between the Hackberry tree and the American Snout, which is stable thanks to the tree’s abundance in Texas, the relationship between the Monarch and the milkweed is mutually precarious.

The Monarch and Milkweed Project is currently conducting research in preparation for if the monarch butterfly becomes listed as an endangered species.

“We are looking at patched-sized dynamics, which is to figure out if monarch butterflies prefer to lay their eggs at a certain milkweed density,” explained Chavez.

He said that the reason behind focusing on milkweed patches is to find out whether they should plant these flowers in abundant concentrations or spread out over a large area.

Additionally, to optimize their strategy of repopulating milkweed to aid the monarch, the team has to identify which milkweed flower is most preferred by the butterfly. Texas has over 36 types of milkweed, and the project is doing a cafeteria study where, according to Chavez, “(We) get hole punches of different types of milkweed, and we put a caterpillar in the center and see where they go; we do this over and over with different milkweed and caterpillars to see if there is a pattern.”

The team’s urgency in identifying the preferred milkweed flower stems from the desire to plant it as much as they can before the monarchs return to Texas and begin laying eggs.

Monarchs spend the winter in Mexico from December to February. In March they start their journey back to Canada. The monarchs will pass through Texas between February and March. In this window of time, the monarchs will arrive and start reproducing. As Chavez explained, “that is why it is important to have milkweed in Texas.”

Moreover, he compared the etiquette of feeding guests in your home with the obligation of Texas to be prepared for the monarchs’ arrival.

“I would say that if you came over to my house, I’m going to make sure you leave my house full; you are not going to be hungry. So whenever the butterflies come through Texas, we want to have plenty of flowers because that is what they eat. We want them to leave here full. They won’t be hungry in Texas, so plant a lot of flowers and nectarine plants for the fall and spring along with milkweed.”

Unfortunately for some monarchs, however, the travel route is like a morbid relay race. The butterflies that wintered in Mexico will not be the ones to complete the full migration path. It takes four generations of living and dying to make it back to Canada.

On the misidentification of the American snout and the monarch, Chavez had these final words.

“We are expecting to see the (monarch) butterflies this year, hopefully more than we have in the past. Our goal is to have the monarch migration as big as the snout nose passing we saw. We want that to be normal again because that is the way we used to see monarchs in the past.”

For more information about the project and the monarch butterfly, go to http://www.utsa.edu/crts/monarch/ or contact Julian Chavez at [email protected]