A conversation with Lewis F. Fisher

Local author and historian discusses his new book on Brackenridge Park

October 25, 2022

Public parks often hold respite, enriching activities and in this case — a history that spans over 12,000 years. For decades, Brackenridge Park has been one of San Antonio’s foremost places for fun and relaxation.

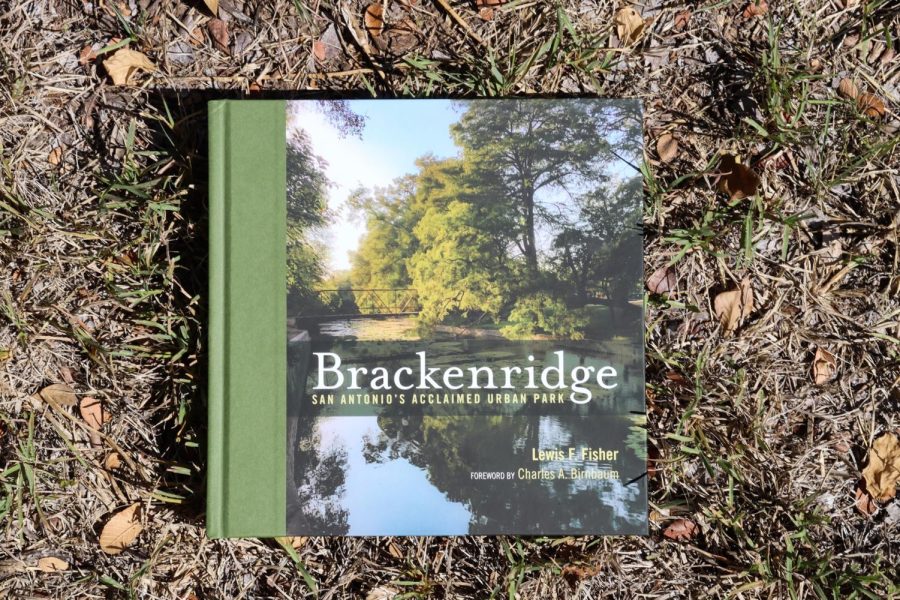

Lewis F. Fisher’s newest book — “Brackenridge: San Antonio’s Acclaimed Urban Park” — is available now from most booksellers. Through over 200 richly-photographed pages, Fisher chronicles the extensive history of the park, the land and some of what Brackenridge Park’s future looks like.

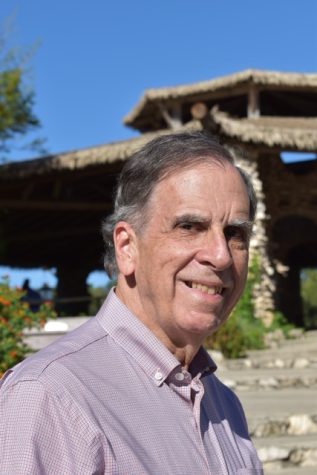

Fisher is many things: a scholar, historian, former journalist and chaser of curiosity. Arriving in San Antonio in 1969 by way of the Air Force, Fisher found himself working at the San Antonio Express-News. Then, in 1971, Fisher started a newspaper, publishing the North San Antonio Times.

Fisher’s first book on San Antonio — “Saving San Antonio: The Precarious Preservation of a Heritage” — was printed in 1996. To Fisher, writing this served as a sort of “realization” about San Antonio’s history. And with the publishing of “Saving San Antonio,” there came a step toward writing other books about San Antonio.

“That was actually inspired by the realization that very little had been known about what really happened in San Antonio … from there, it was a short step toward doing other books about San Antonio. Brackenridge Park was no exception,” Lewis said.

The first part of Fisher’s book starts with an analysis of the indigenous people who occupied the land that the park sits on for well over 12,000 years.

“There are many Native American [and] prehistoric sites within Bexar County, but there is no greater concentration of [them] than within what is now Brackenridge Park. The reason, of course, is the presence of water and trees. There was good hunting,” Lewis said.

The Headwaters Sanctuary sits not far from Brackenridge Park, on what is now the site of the University of the Incarnate Word. The Headwaters make up the spring from which the San Antonio River is believed to come from. This stretch of land is unique, and according to the Headwaters Sanctuary, “the headwaters remain a powerful symbol of the literal and spiritual life-giving essence of water. Flowing or not, they remain, to many, the sacred springs.”

George Brackenridge is the namesake of Brackenridge Park. While his name is celebrated throughout Texas and San Antonio, he was not always viewed in a favorable light in his time — Brackenridge was a Union loyalist during the Civil War. However, Fisher recounts that Brackenridge became involved in several philanthropic ventures after the war.

“In 1866, he started the First National Bank … [the] bank became the only reliable source of large amounts of capital in the city. He was a supporter of education. He held the record for tenure on the University of Texas [at Austin’s] board of trustees. [He was] very strong with public education in San Antonio — he gave the funds for the construction of Brackenridge High School,” Lewis said.

George Brackenridge would eventually donate 200 acres of land to the city of San Antonio to build the park that would immortalize his name. In 1899, Brackenridge Park was created.

A map of Brackenridge Park accompanies each part of Fisher’s book. As time passes in the book, the map grows, becoming more and more familiar. For Fisher, those maps would not have been possible without the research necessary to make this book happen.

“They could not have been drawn without the research that showed what was actually there,” Lewis said. “Until this book came out, there was a poor [and] mixed record of how things fit together.”

This book’s research process was extensive and shows in the array of archival images that paint this park’s portrait.

“Well, the illustrations were the icing on the cake,” Lewis said. “There had been some research on some of the structures in the park for the National Register of Historic Places. But what there had [not] really been was a perspective that showed why they were there.”

Fisher utilized online newspaper archives of the Express-News and the now-defunct San Antonio Light to gain that perspective.

“It would have been very hard to have written this book 10 [or] 20 years ago without these resources available online,” Fisher said. “Even in spite of the pandemic when libraries were [not] open you could sit at your computer and gather that information.”

To Fisher, San Antonio is not like other cities. While the book calls Brackenridge Park “acclaimed,” Fisher notes that the park did not always have the recognition it has now.

“I mention in the book words to the effect that ‘Brackenridge Park has had no respect from park designers or landscape architects elsewhere in the country for years,” Lewis said. “Brackenridge Park developed by a series of local people on a patchwork basis.

Rather unfortunately, the park has fallen into disrepair over the years. Lack of signage and care for the space is prevalent. A portion of the 2017 City of San Antonio Bond Project was put in place to renovate the space around a pump house on the park’s northern end.

“The park developed well in the first two decades. Ray Lambert — a very good park commissioner — developed the park and really gave us the basis of the park that we see now. [But] with the [Great] Depression, in 1931, 60 park workers were let go [and] maintenance declined. Even lesser attention was paid [to the park] and over time it was taken for granted” Lewis said.

In 2008, with help from the San Antonio Conservation Society, the Brackenridge Park Conservancy was created as an independent nonprofit to act as a sort of watchdog to the park. Both groups work together in assisting with the park and its future, and funds have been raised by both groups to assist with work on the pump house.

The Witte Museum will be hosting an exhibit in conjunction with Fisher’s book. The exhibit will be an interactive version of Fisher’s book, with much of the same illustrations from the book on display with several artifacts excavated from inside the park.

“You [will] find the exhibit tracks the book very closely,” Fisher said. “They have a couple of cases of artifacts about the park. Museums provide object-based education and that will further help people appreciate what is in the park.”

As the park stands on the precipice of a safe future, Fisher hopes his book will help people to understand why things are in the park and what they meant.

“I think they will have a much better understanding of how the park is in good hands now,” Fisher said. “And a much better understanding of what the park is and therefore why it is important to preserve it.

The exhibit at the Witte Museum, which was derived from Fisher’s book, is now on display until March 20, 2023. You can listen to the full interview with Fisher on The Paisano Audio’s Spotify page.