SAPD: Abolishing and defunding are not the same

October 16, 2020

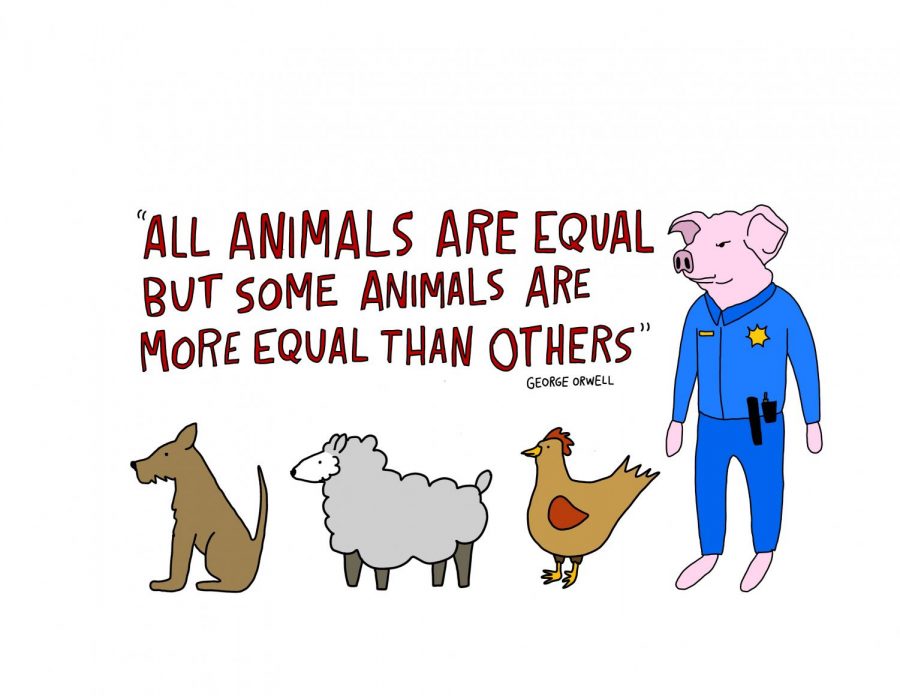

Defunding the police is a referendum on American values and should not be confused with abolishing the police. In short, defunding the police can be described as the reallocation or redirection of funding away from police departments to other government agencies funded by local municipalities. The central idea behind this reallocation is to invest in services that have proven to be more effective in reducing crime than increased law enforcement.

“Last Week Tonight” host John Oliver explained the purpose of defunding the police by saying that “the concept is the role of police can significantly shrink because they are not responding to the homeless, mental health calls or arresting children in schools or to other situations where the best solution isn’t someone showing up with a gun.”

The majority of law enforcement’s time is spent responding to nonviolent crimes. According to the ACLU, out of the 10.3 million arrests made per year, 95% of arrests are for minor offenses including traffic violations, marijuana possession, unlawful assembly and even removing a shopping cart from store premises. Law enforcement handles everything from potholes in the street to mental health checks.

Brooking Institute writer Rashawn Ray argues that “focusing on menial tasks throughout the day is inefficient and a waste of taxpayer money. Other government actors should be responsible for these and receive adequate funding for doing them.”

There seems to be a general consensus that law enforcement is overworked, which ultimately leads to their ineffectiveness in solving violent crimes. One example is Texas, which is below the national average of clearing violent crimes such as aggravated assaults, rapes and robberies. In 2018, Texas law enforcement agencies reported 31.3% of murders, 72.5% of rapes, 80% of robberies and 56.8% of aggravated assaults were not cleared.

Proponents of defunding the police believe such an approach would limit the job description of law enforcement so they can focus on the crimes that are truly a threat to the public’s safety: violent crimes. In stark contrast, a Pew Research survey found that 31% of people believe increasing law enforcement funding would be a more effective solution. However, a study using 60 years of data found that an increase in funding for police did not significantly relate to a decrease in crime.

“So much of policing right now is generated and directed toward quality-of-life issues, homelessness, drug addiction, domestic violence,” Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza told NBC’s “Meet the Press” last week. “What we do need is increased funding for housing; we need increased funding for education; we need increased funding for quality of life of communities who are over-policed and over-surveilled.”

Investing in education equity, affordable housing and work infrastructure has consistently been found to be an effective approach to reducing crime. Yet, since the 1980s, spending on law enforcement has dramatically outpaced that in community services.

For instance, the San Antonio’s Fiscal Year 2021 Adopted Budget gives police $486.5 million out of the city’s $1.287 billion. Spending on housing affordability ($23.7 million) and infrastructure ($99.9 million) pale in comparison to the massive San Antonio Police Department budget.

SASpeakUp 2020 found that respondents most commonly reported in their open-ended responses that public safety should receive decreased funding and infrastructure should receive increased funding. The majority of respondents ranked housing affordability as their top budget priority.

The San Antonio community clearly wants a change; however, real change is limited by two key factors: San Antonio police unions and their police collective bargaining agreement (CBA). In 1974, San Antonio voters approved collective bargaining for police officers. These agreements can last between one to five years and are approved by the City Council.

The problem with police CBAs is that the San Antonio Police Union is in a position to draw out negotiations until they get what they want because they could cause the city’s credit rating to take a major hit. If the city credit score were to drop, it could cost taxpayers tens of millions of dollars in higher interest rates. The 2015 negotiation for the 2016-2021 police CBA exemplifies this abuse of power.

The current police CBA leaves city council with their hands tied on taking immediate action to reallocate police funding to social services because the city is obligated to satisfy the terms of the CBA. San Antonio’s Fiscal Year 2021 Adopted Budget shows CBA-mandated cost increases to SAPD of $12.9 million police funding. After budgeting reduction ($6.2 million), improvements ($1.6 million) and reorganization ($269,000) the net increase to the SAPD budget was $8 million.

An estimated 80% of the SAPD budget are costs tied to the CBA. Two major cost drivers within the police CBA are the mandated yearly wage increase and health care coverage. 62 of the top 100 highest compensated city employees are police or firefighters.

Overall, the bold call for defunding the police may more accurately be referred to as a reallocation of police funds into services that will target the root cause of crime. As activists continue the call for defunding the police, they may need to call for the end of police collective bargaining agreements as a whole.