‘A dangerous time’

March 7, 2023

In “A Talk to Teachers,” written in 1962, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, James Baldwin noted it was “a dangerous time.” It seems timely, now, to try to assess where Texas higher education is, especially in regards to Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Justice (DEIJ), and academic freedom. Republican policies and legislation in this state and across the U.S. have placed these aspects of university education to the fore. In 2021, The University System of Georgia “eviscerate[d] tenure” for academic faculty. Tenure, states Irene Mulvey, the American Association of University Professors President, has always protected academic freedom to “pursue research and innovation and to draw evidence-based conclusions free from corporate, religious, or political pressure.” In Florida, a swift succession of 22 laws passed in 2022 has led to the outlawing of teaching Critical Race Theory and the emptying of libraries under the “Stop WOKE Bill.” Now a new Florida bill, HB 999, would give the state full control over university curricula and hiring, ban DEIJ altogether and end tenure. The question now is if, and how far, will Texas follow suit?

In 2022 SB3 was passed in Texas covering K-12 and removing provisions for teaching topics including the history of Native Americans, the writings of Frederick Douglass, the Indian Removal Act, the Chicano movement and the history of white supremacy. The Intercultural Development Research Association (IDRA) notes in a guide for teachers that the bill “limits the teaching of accurate, comprehensive and truthful accounts of U.S. history, current events and society.” Texas now has 800 bans on books — more than any other state — including titles that deal with gender and sexuality, race, LGBTQ+ issues and reproductive justice. On Feb. 7, Gov. Abbott sent a memo to state agencies announcing that DEIJ initiatives in hiring are considered to be “illegal” because they work to correct historic systemic racial and gender inequities. Under this new decision, only merit is a valid metric in hiring decisions. The UT System’s current statement on DEIJ recognizes systemic inequity: “Underpinning this philosophy is a belief that talent is universal — distributed evenly regardless of gender, race, national origin, ethnicity, age or anything else — but, unfortunately, opportunity is not.” A focus on merit alone, arguably an ableist construct that privileges white people, would discount efforts to redress unequal opportunities that affect minoritized candidates.

On Feb. 22, the UT Board of Regents announced a freeze on DEIJ and stated: “We welcome our elected officials in this legislative session looking into DEIJ policies throughout higher education in Texas we will certainly implement any new policies the Legislature puts in place.” This position raises clear questions about ensuing directives. The statement comes alongside HB 1006, that would explicitly, as Dan Solomon notes, “prohibit the funding, promotion, sponsorship or support of ‘any office of diversity, equity, and inclusion,’ or any office that operates under another name but which supports the goals of diversity, equity and inclusion,” if passed.

This week alone, Texas A&M, Texas State University System and the University of Houston System have all issued statements pausing DEIJ initiatives in hiring. In an email, Renu Khator, chancellor of the University of Houston System, stated, “we stand against any actions or activities that promote discrimination in the guise of diversity, equity and inclusion.” This is the general thrust of these moves, which combine to rearticulate DEIJ, a long-understood remedy for addressing discrimination, as itself discriminatory.

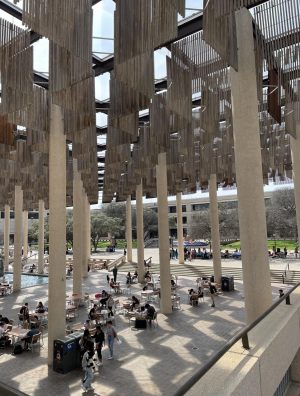

All of this raises questions for UTSA, in particular, a Hispanic Serving Institution with a stated commitment to inclusive excellence. As UTSA President Taylor Eighmy recently briefed at the State Capitol, many of UTSA’s successes are based on graduating, employing and keeping UTSA students in Texas. The UTSA mission states: “UTSA places a focus on advancing prosperity and opportunities for Hispanic communities, and on preparing underserved populations to achieve their dreams of a college education.”

However, a central irony of defending DEIJ programs is that they have not been shown to work particularly well, especially to address intersectional underrepresentation in hiring in terms of race. UTSA’s own figures show a large discrepancy between the UTSA Hispanic student population of 57% and the people teaching them: Hispanic faculty hover between 19 to 20% over the years, while Black faculty remain at 4%, and Indigenous faculty at a worrying 0% in a region where many people are Indigenous. Texas has a higher number of Black people than any other state, at about 13%. In Texas overall, 40% of people identify as Hispanic. In 2020 the San Antonio City Council passed a Resolution declaring racism to be a public health crisis. The head of IDRA, Morgan Craven, noted the link between racism and education: “We continue to see this negative and persistent impact of the long history of racism today because education is a key social determinant of health.” Race is the vector along which other inequities are articulated, affecting disabled people, veterans, LGBTQ+ and lower-income groups. What might these statistics look like without DEIJ in place? The need to ensure that students learn from people like them, and that these students could themselves become professors, are reasons why some might wish to keep DEIJ initiatives.

Education, Baldwin tells us, is always a target of state authority:

“The purpose of education, finally, is to create in a person the ability to look at the world for himself, to make his own decisions, to say to himself this is black or this is white, to decide for himself whether there is a God in heaven or not. But no society is really anxious to have that kind of person around. What societies really, ideally, want is a citizenry which will simply obey the rules of society. If a society succeeds in this, that society is about to perish.”

Baldwin, whose books have been subject to bans in the past, warns that the danger is to society itself. It is always in the interests of capitalist state power to limit what we know, who we learn from and what we can say and think. This is because education is, as bell hooks tells us, fundamentally a practice of freedom. Yes, this is a dangerous time: when has it not been?

Disclaimer: Any opinions expressed here are the author’s and do not represent UTSA or other university faculty